Zuckerberg’s original metaverse vision was right: It needs to be more than online school in 3D

The vision for a multiplatform metaverse makes more sense in a world where few people are using VR headsets.

We need a new way of talking about the metaverse.

When Mark Zuckerberg announced that Facebook was changing its name to Meta Platforms, the company’s vision appeared much broader than what it exhibited in the subsequent months with a hyperfocus on virtual reality and its Reality Labs products like Horizon Worlds and Oculus headsets. In his letter about the rechristening, Zuckerberg emphasized accessibility across a multitude of platforms, which would ensure as many people as possible could join his version of the metaverse.

You’ll move across these experiences on different devices — augmented reality glasses to stay present in the physical world, virtual reality to be fully immersed, and phones and computers to jump in from existing platforms. This isn’t about spending more time on screens; it’s about making the time we already spend better.

–Founder's Letter, 2021 | Meta

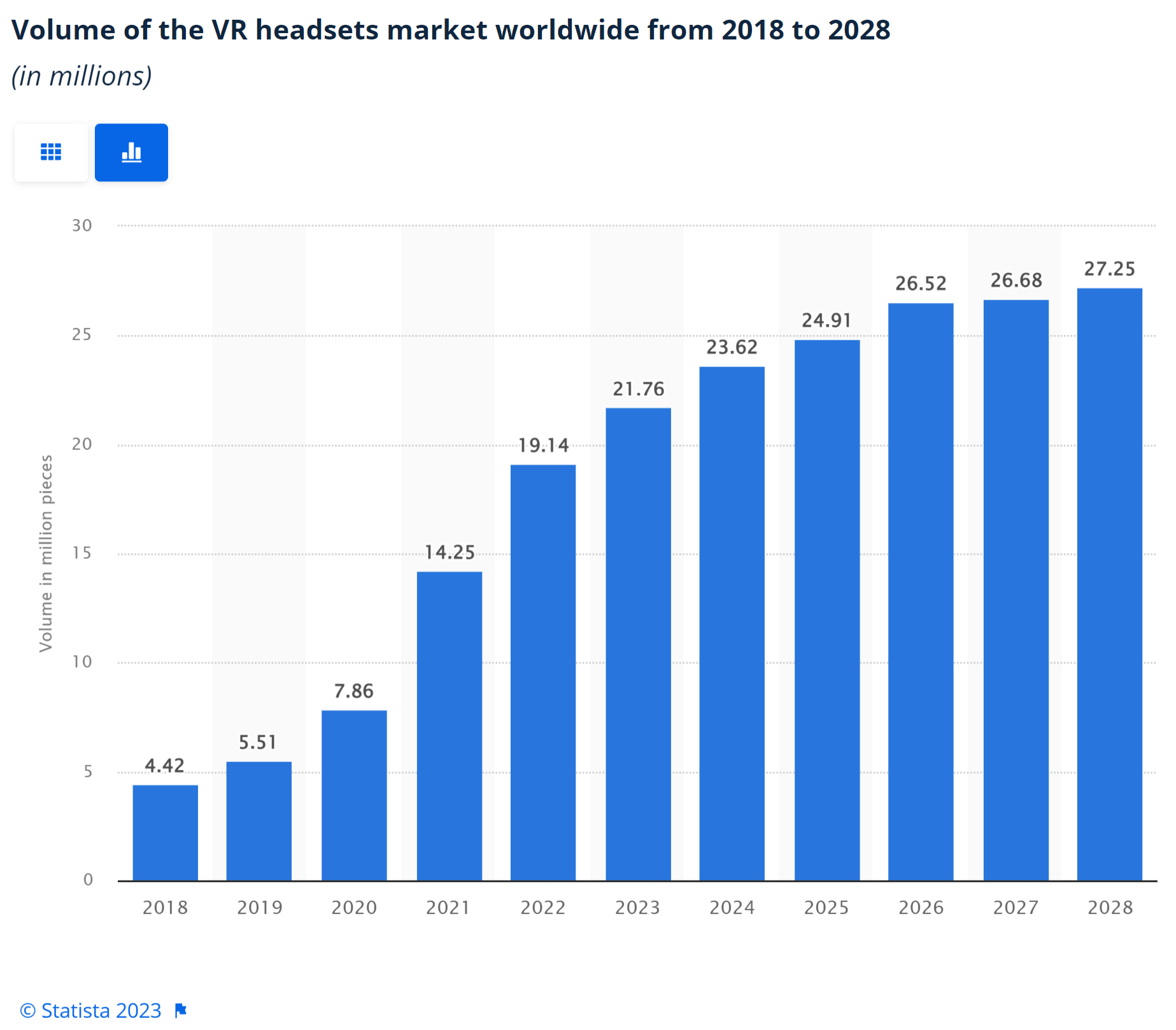

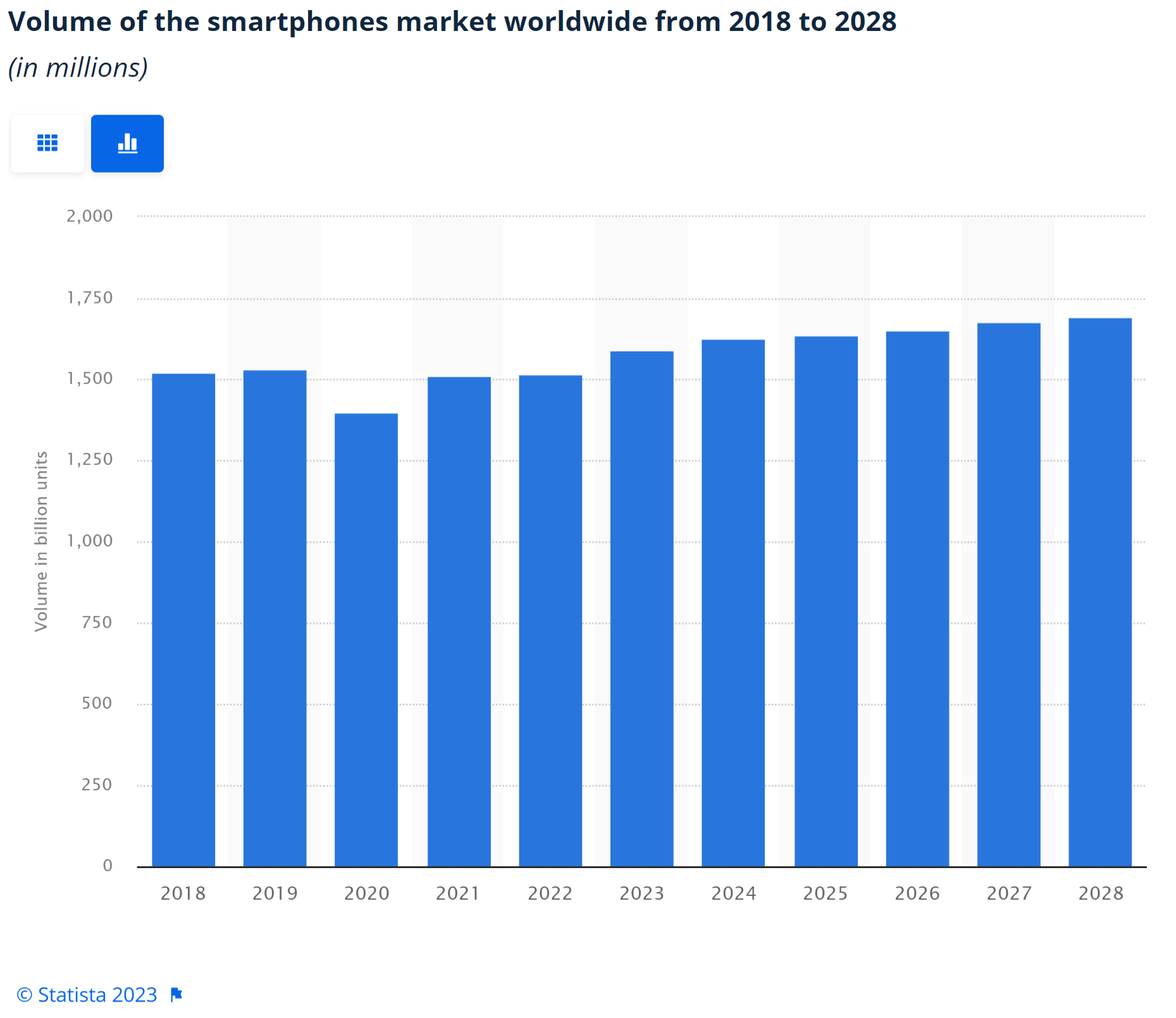

Little has been said since about the role of smartphones, computers and other existing platforms in the metaverse. Instead, the focus has almost exclusively been on VR, despite only a very small fraction of consumers having access to the hardware needed to jump into this vision of the metaverse.

One of the main focuses of metaverse discussions today is about training and education. Banks, for example, are using VR to train employees about how to handle a potential robbery.

Until late last year, Bank of America branch staffers would learn how to handle a potential stick-up through guidebooks and online videos. Today, tellers are immersed in a 3D virtual reality environment, in which a gunman aims a weapon at them or furtively hands them a threatening note demanding money.

The bank measures tellers’ reactions and the time it takes them to respond to a robber’s threat. With those analytics in hand, trainers can do more-targeted coaching, said Michael Wynn, who oversees 3D training for the bank’s Academy Innovations and Training Solutions team.

…

Virtual robberies are just one example of how Bank of America and other large companies like PepsiCo, Walmart and P&G are increasingly turning to VR tools to train staff, host meetings and showcase new products.

–Hands Up, This Is a (Virtual) Robbery! | The Information

Schools are adopting this vision of the metaverse, as well. Particularly in Asia. Schools and governments in South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan are all investing the metaverse for education, Nikkei Asia reported. Schools are investing hundreds of thousands of dollars towards this effort. South Korea’s science ministry has pledged US$166 million towards efforts that include developing a “Metaverse Academy.”

A nonprofit in Taiwan is using VR to help mentally or intellectually disabled children:

Lydia Liu, the [Syin-Lu Social Welfare Foundation’s] director, told Nikkei that its use of the metaverse involves providing a first-person perspective via immersive digital environments to put the public in the shoes of those with autism, letting them experience what autistic individuals encounter in their daily lives.

"Our goal is to evoke empathy and help others understand the discomfort and inconvenience that autistic individuals may encounter," Liu said.

–Metaverse education blossoms in South Korea, Japan, Taiwan | Nikkei Asia

The most encouraging thing about these developments is that they are geared towards increasing understanding and empathy. At its best, the metaverse would ideally enhance our ability to connect and share experiences with people around the world.

But the narrow vision of the metaverse as described in these articles is very limiting in this respect. By reducing the metaverse to virtual reality (two distinct terms that are supposed to be describing different things), most of the world is effectively locked out of the conversation – and likely will be for many years to come.

The term as originally intended did encompass virtual reality, but it was also something more.

Author Neal Stephenson coined the word in his 1992 novel Snow Crash to mean a 3D virtual world that is effectively the next generation of the internet. That was supposed to be the vision of the metaverse today, but the technology is simply not there yet. There are a variety of reasons for this, but the biggest hurdles are perhaps internet latency and headsets. The fact is that it's just not very fun for most people to spend most or even much of their day in virtual reality right now.

In his book The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything, Matthew Ball describes the problem with latency as the biggest network hurdle today:

Latency is the greatest networking obstacle on the way to the Metaverse. Part of the issue is that few services and applications need ultra-low-latency delivery today, which in turn makes it harder for any network operator or technology company focused on real-time delivery. The good news here is that as the Metaverse grows, investment in lower latency internet infrastructure will increase. However, the fight to conquer latency doesn’t just stretch our pocketbooks; it comes up against the laws of physics. To quote the CEO of one leading video game publisher with experience building games for cloud delivery: “We are in a constant battle with the speed of light. But the speed of light is and will remain undefeated.” Consider how difficult it is to send even a single byte from NYC to Tokyo or Mumbai at ultra low-latency levels. At a distance of 11,000–12,500 km, this commute takes light 40–45 ms. The physics of the universe only beat the target minimum for competitive video games by 10%–20%. This doesn’t sound like we’re losing to the laws of physics. But in practice, we fall far short of this 40–45-ms benchmark. The average latency of a packet sent from Amazon’s northeastern US data center (which serves NYC) to its Southeast Asia Pacific (Mumbai and Tokyo) data center is 230 ms.

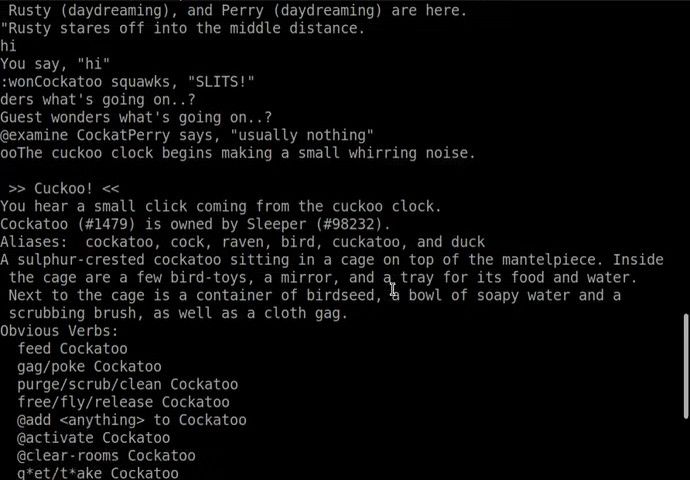

From this perspective, the cross-platform approach that Zuckerberg originally paid lip service to made the most sense for what the metaverse could be today. After all, virtual worlds do not actually need graphics at all to work, much less 3D graphics. Consider the multi-user dungeons (MUDs) of old. These were effectively a combination of chat rooms and text-based adventure games, designed specifically for role playing a la Dungeons and Dragons.

In a grim example illustrating how virtual reality is real, philosopher David Chalmers in his book Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy uses the example of one of the earliest publicized cases of online sexual assault, which took place on the MUD LambdaMOO in 1993.

The case, detailed in a December 1993 article in the Village Voice by Julian Dibbell, involved a person going by the character name Mr. Bungle who programmed a virtual "voodoo doll" to ascribe certain actions to other users. Bungle had the program send text commands to the chat showing one player performing a series of sexual and violent acts against two others. The behavior angered the community, and Bungle was kicked out, although the person later rejoined under a different character name.

The event had real effects on those who were targeted, as Dibbell detailed:

Months later, the woman in Seattle would confide to me that as she wrote those words posttraumatic tears were streaming down her face -- a real-life fact that should suffice to prove that the words' emotional content was no mere playacting.

Chalmers ties the example to virtual realism, the idea that “virtual reality is genuine reality” and “virtual objects are real and not an illusion”—i.e. they are real digital objects, although not really the objects they represent. Thus the experiences in virtual worlds are real, as well.

Virtual realism gives the same verdict. The assault in the MUD was no mere fictional event from which the user has distance. It was a real virtual assault that really happened to the victim.

The challenge of policing sexual assault online is sadly only growing greater with virtual reality. And it is just one area in which the development of the metaverse presents ethical challenges. As Chalmers explains, “There are many social and political concerns about the impact of virtual worlds on society that parallel issues about information technology more generally: inequality, privacy, autonomy, manipulation, resource-intensiveness, and more.”

Consider too the impact of identity:

These many different sources of oppression can intersect. The American legal theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality for the way in which multiple identities can interact: A Black woman’s experience of oppression is not a mere sum of oppression for being Black and for being a woman. Likewise, a lower-class person in a virtual world may be oppressed in ways that don’t derive just from being lower class or from being virtual, but from their intersection. AI systems in virtual worlds may be oppressed in ways quite different from AI systems in nonvirtual worlds. With so many different intersections, the forms of oppression may multiply.

Genuine equality requires removing these oppressive relations among beings of all sorts. A transition to abundant virtual worlds will not be enough to ensure this. Indeed, it may introduce new forms of inequality. As a result, we can’t expect virtual worlds to easily become egalitarian utopias. Still, virtual realism allows us to see how virtual worlds are potentially transformative for at least some aspects of equality.

The LambdaMOO assault shows that these problems do not just exist in 3D virtual worlds. Anywhere people form communities, even if just through words, there are those who are opening themselves up to be vulnerable. These challenges will also continue to increase outside the confines of VR. The more physical and virtual spaces interface, the more vulnerable we become online. The blurring of the lines is arriving, as cyber-utopianists always dreamed, but the dangers are also much more real.

Consider the spate of crypto thefts that have been happening for years now. A record $3.8 billion was stolen in 2022 alone.

This is only possible because technology has reached a point where we can create scarcity with digital objects. This allows us to create money entirely online along with collectables and other virtual objects that can be sold in the form of non-fungible tokens. These are real property, and property can be stolen or destroyed.

Unlike VR, though, many people in developing economies are already trading crypto and increasingly digitizing their lives in other ways. In its 2022 Global Crypto Adoption Index, which takes different use cases into account, Chainalysis ranked Vietnam, Philippines, Ukraine and India as the top four countries. The US rounded out the top five. Among the reasons for this are sending remittances and using it as a store of value when national currencies are less reliable.

People’s lives everywhere are already moving online. The differences between cyberspace and the physical world are shrinking. When those lines shrink to the point of being barely perceptible, this is what we should understand to be the metaverse.

Philosopher Karen Frost-Arnold explains in her book Who Should We Be Online? A Social Epistemology for the Internet:

Most of us live in the “onlife”—a reality in which online and offline are blurred. Of the global population, 59.5% are active internet users. While the majority of the world’s population uses the internet, there are certainly disparities in access and use. Nonetheless, media systems cannot clearly be delineated between offline/old media and online/new media. As Andrew Chadwick puts it, we live in a period of hybridity where online and offline, new and old, are complexly interconnected.

…

What I witness online does not just shape some kind of online avatar that I shed when I log off. Instead, what I experience online shapes my sense of self, my beliefs, my background assumptions, my epistemic practices, and who I trust as a knower throughout my life, both online and offline. There are often no clear boundaries between my online epistemic community and my offline epistemic community.

We are already living in a world of multi-channel retail that leverages online and physical spaces. And much of our social interaction has moved online, from work meetings to chatting with friends. It is no longer unusual for people to start and maintain long-distance romantic relationships entirely online, and the excitement around ChatGPT has people musing about how long it will be before the movie Her becomes a reality.

In many ways, we are already rapidly bouncing in and out of virtual spaces every day, just as Neal Stephenson imagined we would. It is just not in the way he imagined it. We may eventually reach a point where we really are regularly entering 3D spaces, complete with VR goggles or some other piece of tech (booths full of screens or projected images could negate the need for an uncomfortable headset, for example). But it will take many years to iron out all the challenges highlighted by Matthew Ball.

In the meantime, people all over the world are already sharing our virtual spaces with us on a variety of devices and in a variety of different ways. They deserve to be counted as part of the emerging metaverse, whether or not they can splurge on something like the upcoming $3,000 Apple mixed-reality headset.

References

Ball, Matthew. 2022. The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything. First edition. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company.

Chalmers, David John. 2022. Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy. First edition. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Frost-Arnold, Karen. 2023. Who Should We Be Online? A Social Epistemology for the Internet. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.