Trade is changing. Is the world still flat?

In 2005, Thomas Friedman said trade made the world flat. Political winds are pushing the other direction, but technology has other ideas.

Since political commentator Thomas Friedman declared in 2005 that the world is flat, the political winds and trade trends driving globalization have seemed set on proving him wrong.

That technological trends have brought people around the world closer than ever before is nothing new, and it has been happening for all of human history. Yet while innovations like refrigeration and shipping containers helped the exponential acceleration in globalization through what Manfred B Steger terms “object-extended globalization”, the evolution of communications technology has resulted in more global interconnectedness through “disembodied globalization”, with the exchange of ideas and media online.

This is a newsletter about how those two types of globalization have become intertwined in the digital age as we spend more of our lives in virtual spaces. It follows news related to some broad trends:

- How open or closed are societies becoming in response to digital globalization?

- What impact does digitization have on economic interdependence?

- How much of the economy is contained entirely within digital environments?

Over the past decade, much has been said about the decline of globalization, but of course digitization and online exchange has sped up. This was especially noticeable during the Covid-19 pandemic, which seems to have proved two contradictory ideas concerning online life:

- It is easier than ever before live much of our lives in virtual worlds as everything from entertainment to money can now be produced, managed and exchanged by anyone with a computer from almost anywhere in the world.

- The virtual world remains a poor substitute for meeting in person and exploring physical spaces—so far.

So is globalization really slowing down? By traditional measurements it is. The Economist had this to say last year:

Even before the covid-19 pandemic there were ample signs that globalisation had become slowbalisation. The share of American firms’ revenues that came from abroad was mostly flat; profits earned abroad were falling. Flows of trade and FDI had stagnated. One reason was automation, which reduced the labour intensity of manufacturing and therefore the competitive advantage of lower-wage countries that had become offshoring hubs in the 1990s and 2000s. Another was that wages in those countries rose.

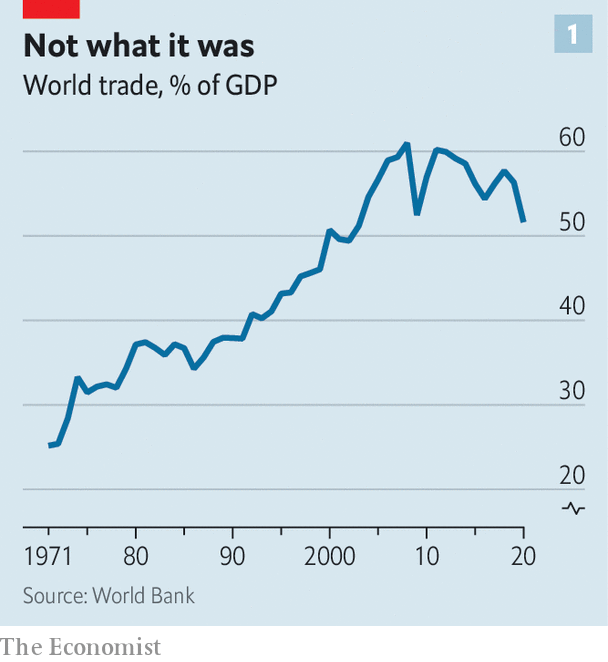

It also presented World Bank data showing a clear decline in trade as a percentage of GDP.

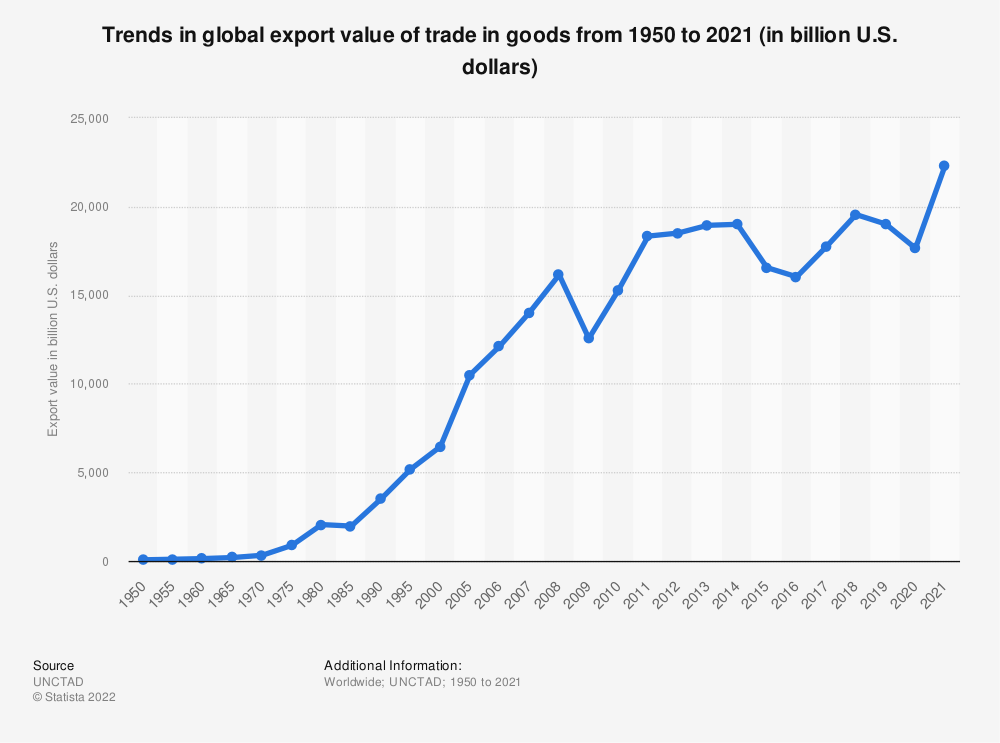

There's no denying that trade had a rough 2010s. In case you missed it, there were countless think pieces in the mid-2010s about it. Still, while trade has not kept up with economic growth, the total value of exports by the end of the decade was little changed from 10 years prior and then jumped during the pandemic.

The total value of exports from 2020 to 2021 was nearly twice the difference between 2010 and 2020. Information technology had accelerated the pace of change, and changes in trade flows have fluctuated much more than was the norm for the latter half of the 20th century.

However, one challenge in measuring globalization solely through economic data is that not all online exchange is easily captured in GDP. Consider cross-border gameplay in online video games—which extract no extra value from customers whether they stay confined in their own countries or not—or digital media and software piracy, which remains rife in many countries where incomes are too low or legal services are unavailable.

Some of this activity is captured in GDP, of course. These exchanges are happening over products and infrastructure that people pay for in one way or another. As George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen puts it:

Let’s not forget that you do in fact pay for Facebook access, indirectly, when you pay for your cable connection, your iPad, and your smart phone. including the monthly bill, all of which are part of measured gdp. The more value Facebook brings you, the more you would be willing to pay for these goods and services. The same is true for Google and the like. So Facebook and other internet services are part of a bundled package of market value, but that is very different from claiming they are not measured in gdp at all.

Yet Cowen has also described himself as a “happiness optimist but a revenue pessimist”, an attitude that comes from the seemingly increasing disconnect between revenue and well-being.

Technological transformation still matters—it has, after all, greatly sped up globalization—it just does not matter as much as it used to. Bradford DeLong, an economist at Berkeley and author of Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, made this point to Cowen on the podcast Conversations with Tyler:

Now, the underlying technology-driven forces of production are continuing to change, and are continuing to change a lot, but in some sense, we think it means less simply because our needs are biologically much less urgent.

Many of our “less urgent” needs are now being served digitally. As tech entrepreneurs try to envision a Web3 world of non-fungible digital goods powering a metaverse in which we can spend much of our daily lives, we may be growing towards a larger digital community. But three decades after the creation of the World Wide Web, the forces that created Friedman's “flat world” have also created some inherent frictions.

These frictions have pushed governments to erect walls to try to slow or reverse the pace of globalization. This includes increasing barriers to immigration and cutting off access to internet resources—or cutting off internet access completely in some cases.

The impulse to reduce the flow of people—embodied globalization—has been exacerbated by a backlash among some who see trade as eroding the rights of workers at home. Security concerns have have also made the place of origin for all the gadgets we use a more political, in some cases leading to a kind of new mercantilism.

These trends have made everyone acutely aware of the fact that underpinning ideas of a cyber-utopia are people and components in the physical world.

Many emergent technologies today will impact the lives of people around the globe in ways that are not yet understood.

These are the trends that Trading Places aims to address. It is about trading the physical for the digital, but also about how the places where we trade are changing.

In traditional newsletter fashion, you will get updates on news related to these topics. Original content will also look at these trends through three lenses.

- Historical: How did we get here?

- Analytical: What does this mean for the future?

- Philosophical: Why should we care?

Welcome to Trading Places. I hope you enjoy your stay. In the metaverse, we're all digital nomads.