Apple’s Tim Cook just can’t quit China, but Asia expansion is a political necessity

Where iPhones are made matters now more than ever – and Apple knows it.

Where your iPhones are made matters, and Apple knows it. It’s just not ready to admit it – at least not in words.

Over the past few years, the politics of supply chains has been made painfully obvious. There has perhaps never been more awareness about the semiconductor industry, how it works, and where it is concentrated than at this very moment. That is why Apple was quick to become the first major customer of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co's (TSMC) new plant in Arizona, which is expected to start mass-producing chips next year.

For its part, TSMC is not very happy about the politicization of its industry or its home country’s position in the world. The company only reluctantly started building a plant in Arizona with promises of subsidies, although it is now upset about conditions attached to the US government handouts, like profit-sharing and the potential to expose corporate secrets.

Meanwhile, the Taiwanese government has been asking the US to rein in political rhetoric about preparing for an invasion from China. A former national security advisor telling Semafor last month that the US would never let China get a hold of Taiwanese chip factories, suggesting the US would sooner destroy them, did nothing to calm nerves.

The stakes for Apple are not quite as dire, but the company has long had a “China problem” that it is seeking to rectify amid heightened political tensions. The tech giant has been scrambling to look for new opportunities in other Asian markets, and in India in particular.

Apple’s iPhone production in India jumped 65% last year, and the company is trying to grow its consumer base in the country with a new retail store as part of a strategy that it hopes could be a virtuous cycle of consumerism.

The move isn’t surprising given Chief Executive Tim Cook in February called India a major focus for Apple, adding that the company is putting a lot of emphasis on the market. On the call, Apple said it posted record iPhone revenue in India in the December quarter, though they didn’t give a specific figure, even as overall revenue declined.

It is no secret that Apple has been growing its manufacturing base in India as it works on a China + 1 strategy. But this narrative has overshadowed India’s steady climb up the luxury ladder over the past few years, and the opportunity it presents for Apple to find the next lucrative market similar to China.

Making iPhones and then selling them in India ensures a smooth supply chain—a page directly out of Apple’s massive success in China over the past decade. Daniel Ives, an analyst with Wedbush Securities, believes that now the company will have “skin in the game” building out production in India with retail success along the way.

–For Apple, India Is the Next China | WSJ

Not all of Apple’s eggs are going in the India basket, of course. It could also be producing MacBooks in Vietnam as soon as this year, and eventually even making computers in Thailand, where it already assembles the Apple Watch.

"Ideally, Apple asked us to set up facilities in Vietnam for MacBooks, following in the footsteps of other Apple suppliers, but we offered an alternative option of building the product at our Thailand plants, which still have a massive space that can be reserved for the client," a senior executive at one of the suppliers told Nikkei Asia. "As MacBook assembly will begin in Vietnam first, we could support the components from our Thailand plants, too. ... It will only take two to three days of logistics and custom clearance."

–Apple in talks with suppliers to make MacBooks in Thailand | Nikkei Asia

That Apple is currently so embedded in and reliant on China is of the company's own making. Despite rapidly expanding production capacity in other markets, Apple will never talk about its supply chain in China as a “problem.” It clearly has become a political liability, but it has long been a very lucrative one.

In January, Patrick McGee did a deep dive for the Financial Times into how Apple became so entrenched in China. As it happened, much of the skilled labor and economic clustering on which many electronics giants have come to rely was built in large part because of Apple.

Over the past decade and a half, Apple has been sending its top product designers and manufacturing design engineers to China, embedding them into suppliers’ facilities for months at a time.

These Apple employees have played integral roles co-designing new production processes, overseeing the minutiae of manufacturing until things were up and running, and keeping close tabs on suppliers to ensure compliance.

Apple has also spent billions of dollars on custom machinery to build its devices, developing niche expertise that its rivals did not even know about, let alone compete with.

It has transformed the company and the country. “All the tech competence China has now is not the product of Chinese tech leadership drawing in Apple,” O’Marah says. “It’s the product of Apple going in there and building the tech competence.”

–How Apple tied its fortunes to China | Financial Times

Recent events are not the first time Apple's manufacturing operations in China have been mired in controversy. It is perhaps only because of Apple that Foxconn became infamous for its working conditions in China.

Simply changing countries is not going to solve worker abuse issues. India and Vietnam are not bastions of human rights, and one reason companies started looking for new markets for production was because wages were rising in China.

But new political considerations in commerce open up a new front of criticism for multinationals to guard against. Concerns about national security are not unreasonable, but they have also sometimes been blown out of proportion.

In 2018, Bloomberg Businessweek reported that China had embedded malicious chips on server boards that affected nearly 30 companies, including tech giants Apple and Amazon. The companies denied the allegations in the story, as did the National Security Agency, and called for a retraction.

Bloomberg has remained committed to the story and even did a followup in 2021, but the reports were widely disputed and nothing much ever came of them.

The story reflects both the very real concerns in cybersecurity circles about the threat from China, but also the difficulty of conveying an imminent threat to the public.

Even after Donald Trump initiated a costly trade war with China, the world has been spared the massive disruption and economic havoc that would be wreaked from full-scale decoupling.

In his book The Digital Silk Road: China's Quest to Wire the World and Win the Future, Jonathan Hillman outlines the threats posed by China-dominated supply chains. But in addition to describing the traditional fears about Chinese-designed systems possibly granting the national government remote access to sensitive systems, Hillman notes that many vulnerabilities in Chinese hardware and software are not necessarily deliberate:

As the internet expands ever further into the physical world, security remains too often an afterthought rather than a primary selling point for consumer devices. “Being first to market is paramount,” explains DeNardis. Designing devices that are more secure and can be patched in the future when vulnerabilities are discovered requires more time and money. These incentives suggest that companies will keep security to the bare minimum until consumers or regulators demand otherwise. Nor are these risks limited to Chinese companies. As cybersecurity expert James A. Lewis observes, “Chinese actors appear to have little trouble accessing U.S. data and devices even if they do not use Chinese services or were not made in China.”

Cheap devices are the most rife with security flaws, whether from malicious intent or not. Cybersecurity experts have been warning consumers about cheap smartphones for years. In a paper published in February, researchers from the University of Edinburgh and Trinity College Dublin found that handsets from Xiaomi, Oppo and OnePlus (also owned by Oppo) transmitted a disturbing amount of identifying personal information to third-party domains without consent compared with non-Chinese brands.

As companies domiciled in China, they do have political incentives to ensure they have certain data on hand if requested by the government. But they also lack some of the financial incentives to ensure their smartphones have the most up-to-date security. Smartphone development happens rapidly in China, and there is much less emphasis on servicing phones years into the future – a point of competition for Apple, Samsung and Google.

Apple is still the gold standard when it comes to updating old hardware with new software. And the company has more recently tried to paint itself as a champion of user privacy and security as people have grown more skeptical of internet giants like Google, which still makes nearly 80% of its revenue from advertising.

But Apple’s promise of protecting user privacy has increasingly rung hollow in China, where it has set up local servers to house data of Chinese customers – in compliance with data localization laws – with the iCloud encryption keys also stored in the country.

Apple customers in China are out of luck when it comes to privacy protections against the government. But complying with China's strict data governance rules has not been a good look for for Apple. Google has the “good” fortune of being banned in the country, so it is a non-issue for the company (efforts to build a new search product for the market died just months after it was leaked to the public).

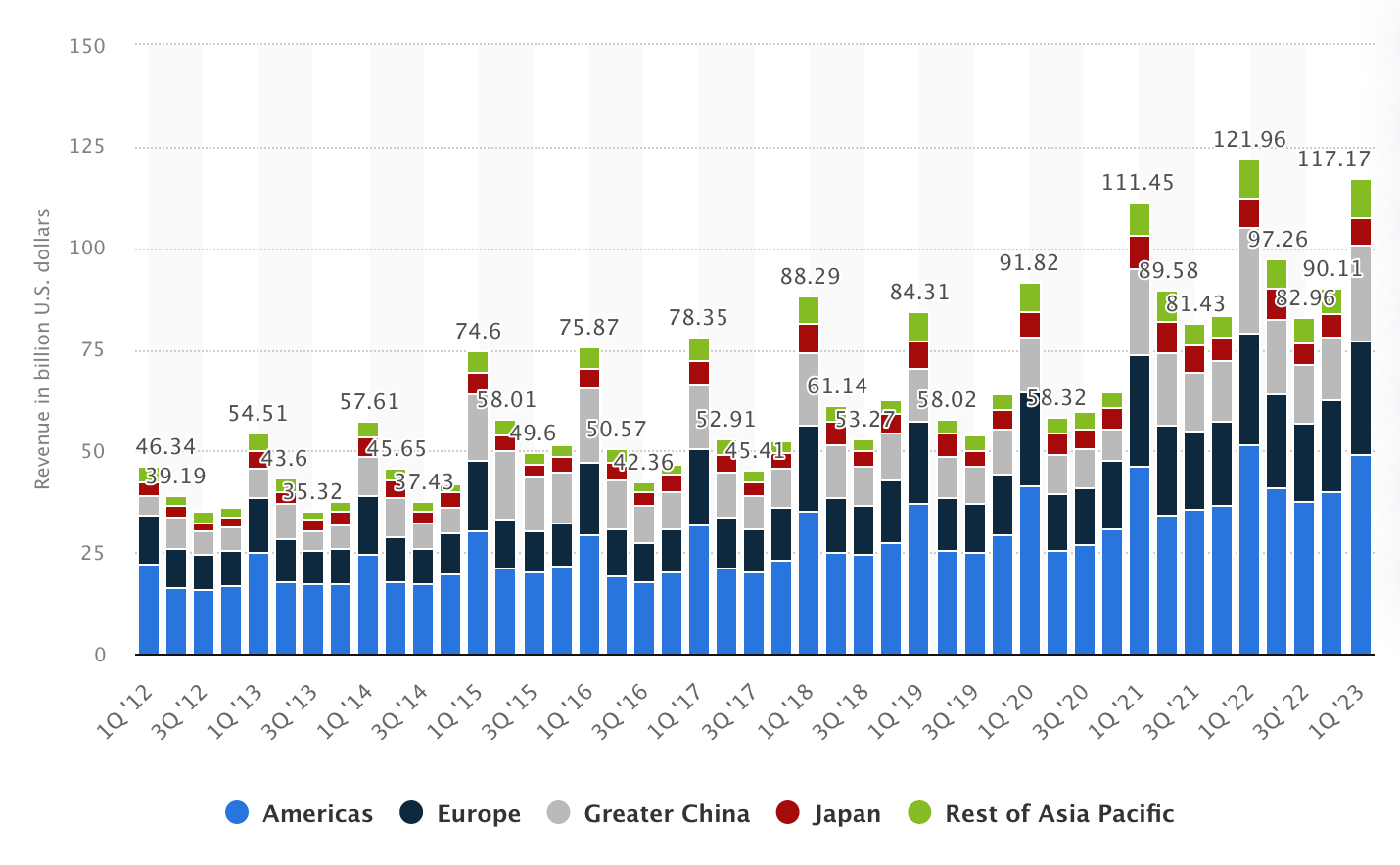

Diversifying supply chains will be a slow process. In the meantime, Apple needs to stay cozy with China. The vast majority of its products are still made there and it has immense commercial interests in the country – Greater China accounts for about a fifth to a quarter of company revenue, depending on the sales period.

Apple's efforts are paying off. The brand and CEO Tim Cook remain enormously popular in the country. But Cook’s recent trip to Asia just put the company’s dueling interests on international display.

After Cook spoke at an economic forum in Beijing at the end of March, he visited India this month and met with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, committing to further investment in the South Asian nation.

No matter where Cook goes, though, China is watching: Chinese netizens closely monitored his moves in India and discussed them on social media.

“Cook showing up [at the new store] means he is giving priority [to the Indian market],” wrote Weibo user Tuzhi on the Chinese microblogging platform on Wednesday.

–Chinese social media closely monitors Apple CEO Tim Cook’s trip to India amid concerns over supply chain shift to South Asian nation | South China Morning Post

If Tuzhi is anxious about what this means for the future of Apple, he can rest easy knowing he's not alone. Apple separation anxiety seems to be a global phenomenon.

References

Hillman, Jonathan E. 2021. The Digital Silk Road: China’s Quest to Wire the World and Win the Future. Harper Business.

Liu, Haoyu, Douglas J. Leith, and Paul Patras. 2023. “Android OS Privacy Under the Loupe -- A Tale from the East.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.01890.