Bluesky vs Threads: Decentralization and fostering a resilient global public sphere

At its peak, Twitter was arguably the closest thing the world had to a global public sphere, uniting diverse voices across geographical boundaries and amplifying marginalized issues.

Recent fractures in the social media landscape have cast doubt on the realization of a truly inclusive global forum. Even long before it became X, Twitter was imperfect in providing a “digital town square.” Yet the emergence of alternative platforms—which have been finding their footing in the wake of the mass exodus following the re-election last fall of Donald Trump to the US presidency—offers a glimpse into how technology could play a more constructive role in fostering global dialogue.

Two events in the past year show how this landscape is evolving. First, the emergence of two Twitter alternatives, Meta Platforms’ Threads and Twitter spin-off Bluesky, offers competing visions for the future of microblogging. Second, the so-called TikTok ban in the US, intended to force ByteDance to divest its US operations, led many American users to briefly migrate to Xiaohongshu (aka RedNote), a platform designed for mainland China with explicit censorship policies.

The Threads vs. Bluesky debate raises fundamental questions about content moderation, decentralization, and the role of algorithmic curation. The TikTok ban begs the question of whether there is a solution to the perceived "brain rot" of centralized platforms or whether we are resigned to take whatever we get from Big Tech companies.

Efforts are already underway to add a TikTok-like experience to Bluesky's underlying AT Protocol.

The core technological debate between Threads and Bluesky centers on openness: the fundamental choice between platforms and protocols.

Threads incorporates elements of ActivityPub, the decentralized protocol powering Mastodon, but decentralization is not really part of Meta’s DNA. Bluesky, conversely, was built from the ground up to be a decentralized version of Twitter using its own open-source AT Protocol.

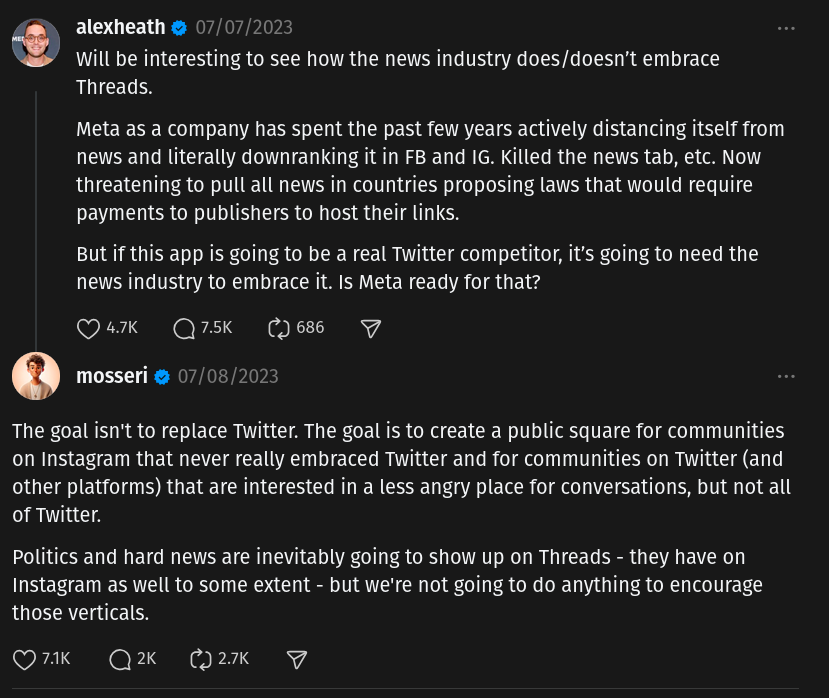

This competition raises important social questions about the purpose of these kinds of platforms. Meta’s cynical approach to news content on Threads has fueled Bluesky's popularity. Adam Mosseri, head of Instagram and Threads, responded to the deputy editor of The Verge that the new microblogging site was “not going to do anything to encourage” political content or hard news.

This would seem to be at odds with the very idea of microblogging, where the sharing of short bursts of information led these platforms to serve as rapid broadcast systems for breaking news.

The commodification of news is intrinsically linked to the need for timely information amid the rise of globalization.

With the expansion of trade, merchants’ market-oriented calculations required more frequent and more exact information about distant events. From the fourteenth century on, the traditional letter carrying by merchants was for this reason organized into a kind of guild-based system of correspondence for their purposes. The merchants organized the first mail routes, the so-called ordinary mail, departing on assigned days. The great trade cities became at the same time centers for the traffic in news; the organization of this traffic on a continuous basis became imperative to the degree to which the exchange of commodities and of securities became continuous. Almost simultaneously with the origin of stock markets, postal services and the press institutionalized regular contacts and regular communication.

–Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere

Technologies that contributed to making the world feel a bit smaller were embraced early on by the news industry. Think of the telegraph, airplanes, and, yes, the internet.

Social networks are now a primary medium for the “continuous” and “regular” communication vital for modern markets. But Threads’ approach to news begs the question: If there isn’t an immediacy to what you're telling me, why are you telling it to me in this way?

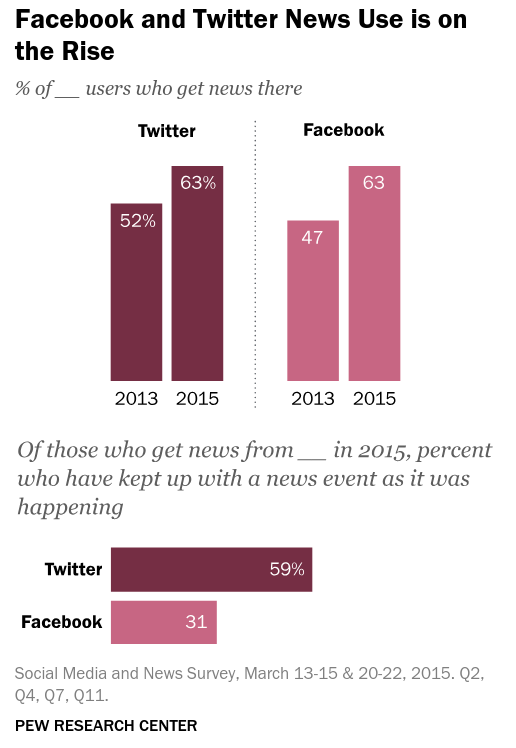

In 2015, Pew Research found that nearly 60% of Twitter users got news on the platform while it was still breaking, compared with less than a third of Facebook users.

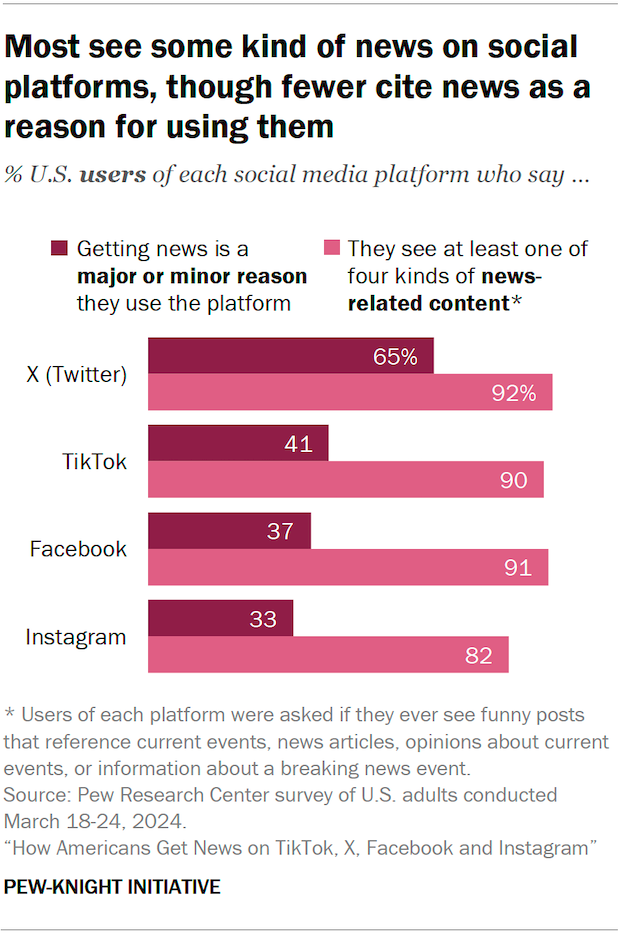

Even today, X remains a bigger destination for news than other social networks and is significantly more likely to be seen as a “major or minor reason” for using the platform.

In the current fragmented social media landscape, Bluesky offers an opportunity to foster a more resilient public sphere.

The AT Protocol addresses a key problem of decentralized platforms: maintaining a unified platform. This has not been without controversy, though. This cohesiveness stems from how the protocol works, and the fact that right now it is not really all that decentralized.

When users log into Bluesky, that content is largely coming from servers owned by Bluesky Social, the company. The AT Protocol follows an approach that ActivityPub developer Christine Lemmer-Webber describes as a “shared heap” system—a global network that pushes everything to a single data graph that users sift through themselves. Usenet is an early example of this type of architecture, which requires a server or node to fetch all the relevant content and keep it in one place.

This is in contrast to what Lemmer-Webber calls a message-passing system, such as email or ActivityPub, where specific content is pushed to people who subscribe to it.

Lemmer-Webber is critical of Bluesky describing itself as “decentralized” because of the costs of setting up a complete node that separately hosts all Bluesky content. This is prohibitively expensive for most individuals, whereas many people can and do host their own Mastodon servers for personal use.

As a Twitter replacement, though, Mastodon is weak. Mastodon is great for operating within specific communities that can also have some interaction with a broader network. But ActivityPub cannot offer the “firehose” effect of surfacing diverse content across different contexts all at once. This is something that Twitter did well, and it is something that Bluesky aims to replicate through a protocol that is open for anyone to use for any application.

As a network, Twitter reflects what Alice Marwick and danah boyd refer to as context collapse, in which users present a single identity to a diverse audience. This can be a challenge for users to develop a persona to fit a particular social network, but it also facilitates cross-contextual content discovery, which can be beneficial for activities such as news gathering and activism.

This technical approach has pitfalls, though. Decentralized social networks have often been held up as solutions to state censorship. In the case of ActivityPub or the Nostr protocol, it is relatively cheap to set up a private instance or relay that may not be censored in a particular place.

People in China, for example, have created their own communities using Mastodon. The larger ones are censored, but people with the know-how could set up their own private servers and interact with users of those communities. Or they could sign up for a different server that is not blocked.

People can also easily set up a Nostr relay that would not be blocked in China or other censorship-heavy locations. While Nostr, like AT Protocol, uses the “shared heap” approach that Lemmer-Webber described, it does not guarantee users will see all content. You will only see the content that makes its way to the relays you subscribe to.

Anyone with the resources could theoretically set up a full-network AT Protocol relay, but operating one at scale would likely require a lot of resources, which means the network is inherently more centralized than solutions like ActivityPub or Nostr. This also means it is easier for censors to target.

Lower-cost solutions are good for avoiding detection and censorship, but not great in situations where a person may need a holistic view of a network.

Crucially, technological solutions alone cannot cure social ills. Decentralized architecture does not eliminate toxicity or mindless entertainment.

When it comes to toxic or dangerous content, Bluesky is working on giving users algorithmic choice, letting people publish their own algorithms that filter or recommend content according to their liking. This will not solve the issue of people staying within their own filter bubbles, but this is a challenge inherent to all social networks.

This brings us back to Xiaohongshu and TikTok. The burst of popularity that Xiaohongshu saw in the US ahead of the TikTok ban taking effect underscores the difficulty in fostering a more constructive relationship with social media.

Driven by anger over an attempted ban of an app the government saw as a potential tool to collect Americans’ data and manipulate the content people see in their feeds, many users flocked to Xiaohongshu, where censorship, propaganda, monitoring, and data collection are explicit parts of the package.

The average social media user is unconcerned with participating in a global public sphere. Many platforms function primarily as vehicles for entertainment, with news providers as mere veneer.

This blending of entertainment and news mirrors the “pseudo-contexts” warned against by Neil Postman in Amusing Ourselves to Death, where important information is trivialized by the form of its delivery method (the medium is the message).

Microblogging platforms like Bluesky, whether decentralized or not, cannot solve for that. The best they can do is maybe broaden the scope of who gets to be part of the conversation.

Lemmer-Webber takes issue with Bluesky's description as a decentralized network, preferring instead to say that it offers what the company itself described as a “credible exit.” The fact that it is an open-source platform built on top of an open protocol makes it “billionaire proof,” as CEO Jay Graber said.

However you frame it, the network has the capacity to grow more decentralized over time, and that could make for a more enduring digital public sphere.

In The Global Public Sphere, Ingrid Volkmer distinguishes between “networks of centrality” and “centrality of networks.” The former emerges from monitoring information distributed for consumption, such as news media. The latter comes from discursive engagement, typically through user-generated content, such as social networks.

A global public sphere, Volkmer argues, emerges from the interplay of the two. We consume news and other information in networks of centrality and then discuss how to view and use that information in the centrality of networks.

What emerges is a type of “reflective interdependence,” through which world views are shaped in discourse across borders.

In an era of global discourse, we should want more democratized digital spaces. Postman’s warnings from four decades ago illustrate why it isn’t enough to just stick TikTok-like apps on top of the AT Protocol. But that isn’t a bad start.

A Twitter or TikTok with the capacity to be more decentralized, is billionaire proof, and offers a credible exit strategy is certainly better than what we’ve hitherto resorted to in managing our public online lives.